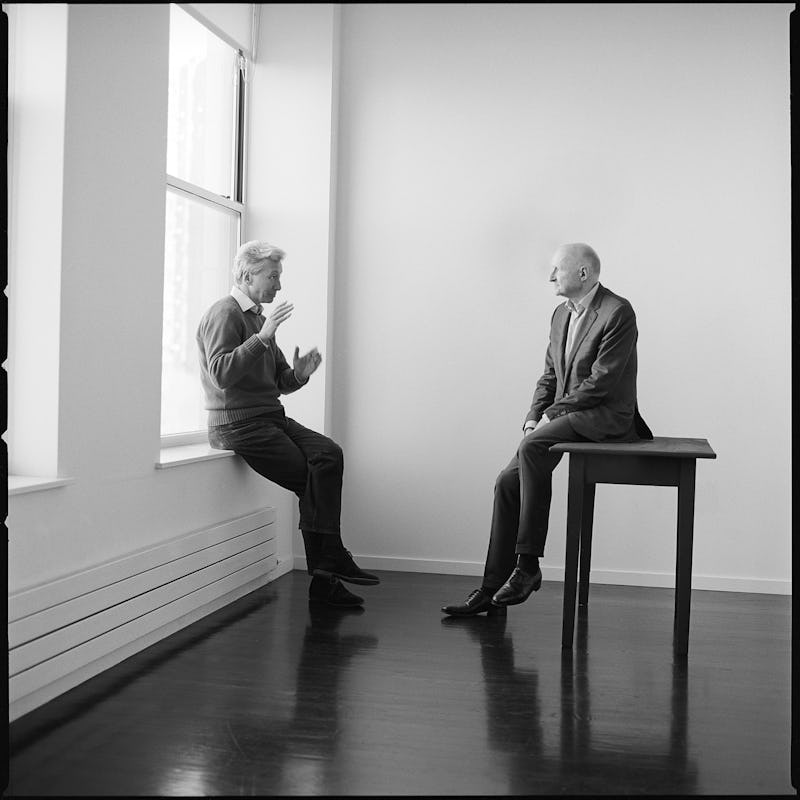

Dominique Ropion photographed by Brigitte Lacombe

Dominique Ropion photographed by Brigitte Lacombe

Odyssey of a Perfumer:

Dominique Ropion

Frédéric Malle makes no secret of his passion for the “Seventh Art,” and knows how to bring this passion into his job as a perfume publisher. Building close long-term working relationships with his authors, he speaks with precision about each one’s particular approach to composition. So when he compares Dominique Ropion, one of his star perfumers, to Stanley Kubrick, one of the greatest American directors of the twentieth century, our curiosity is obviously aroused.

Frédéric Malle and Dominique Ropion first met at Roure-Bertrand Laboratories more than thirty years ago now. Since the creation of Editions de Parfums twenty years ago, the two have developed a particularly strong bond. One of the world’s greatest perfumers, Ropion has already composed nine perfumes for the publisher’s collection, including Une Fleur de Cassie in 2000, Carnal Flower in 2005, and the sublime and already legendary Portrait of a Lady in 2010.

The eclecticism that emerges from their collaboration testifies to Ropion’s unusual ability to excel in all types of perfume, where the majority of perfumers quickly become specialists in a particular genre (masculines, orientals…), which then comes to encapsulate their talent. Ropion’s versatility is the first point the perfume publisher sees in common between the perfumer and Stanley Kubrick.

A movie still from “2001: A Space Odyssey” by Stanley Kubrick (1968)

A scene from the movie “Barry Lyndon“ by Stanley Kubrick (1975)

The first parallel Malle puts forward between perfumes and genre films is the modesty of great authors who, adopting a genre framework and following its conventions, somehow also manage to transcend this chosen genre and make it serve the ends of their art.

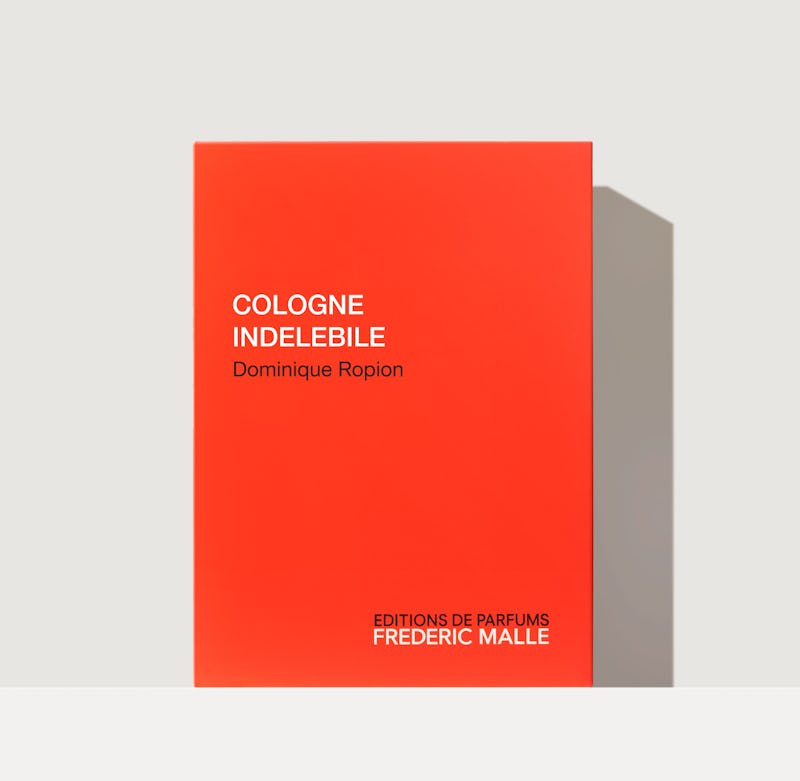

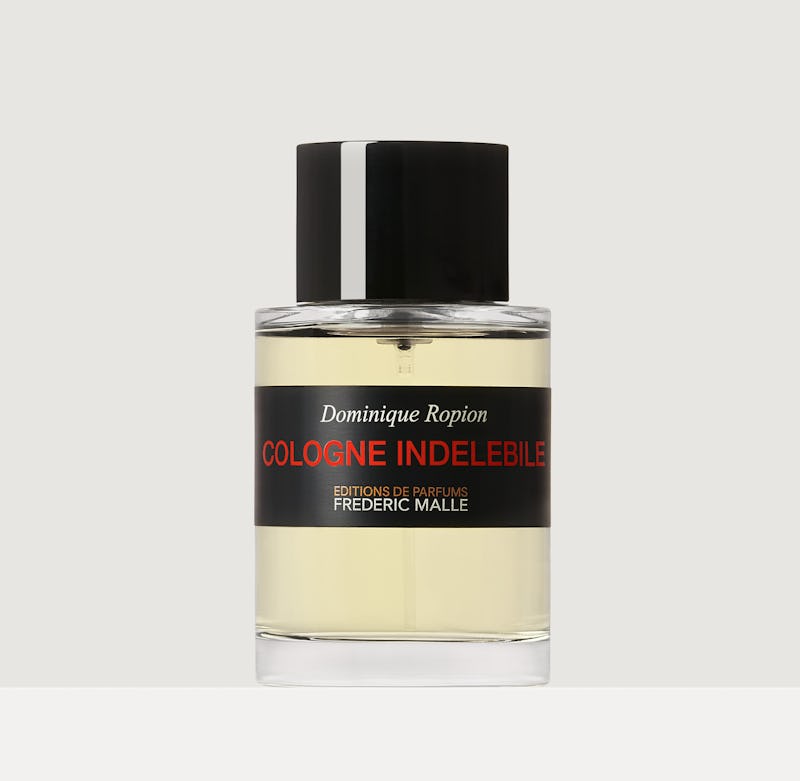

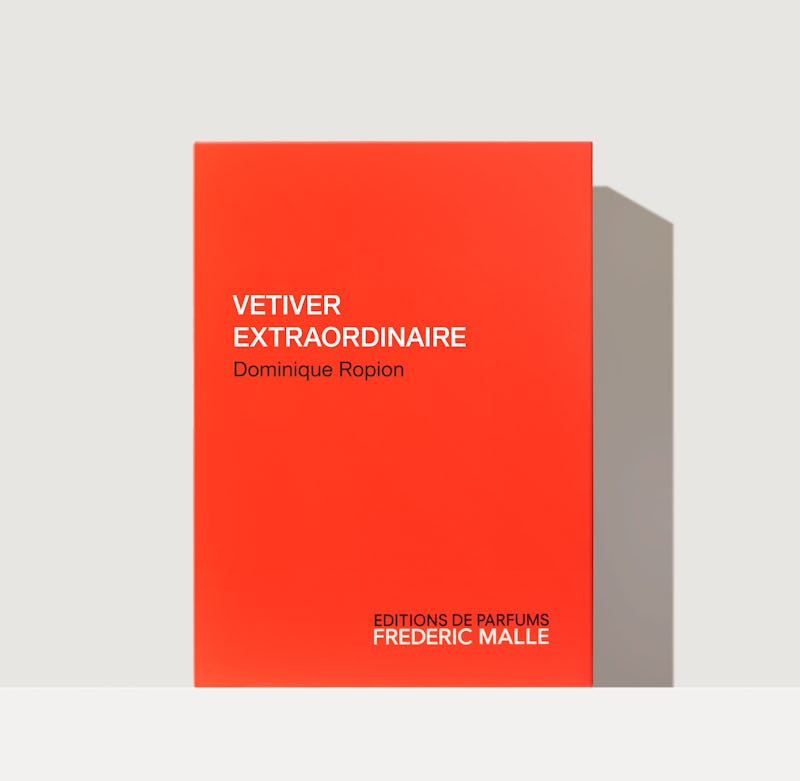

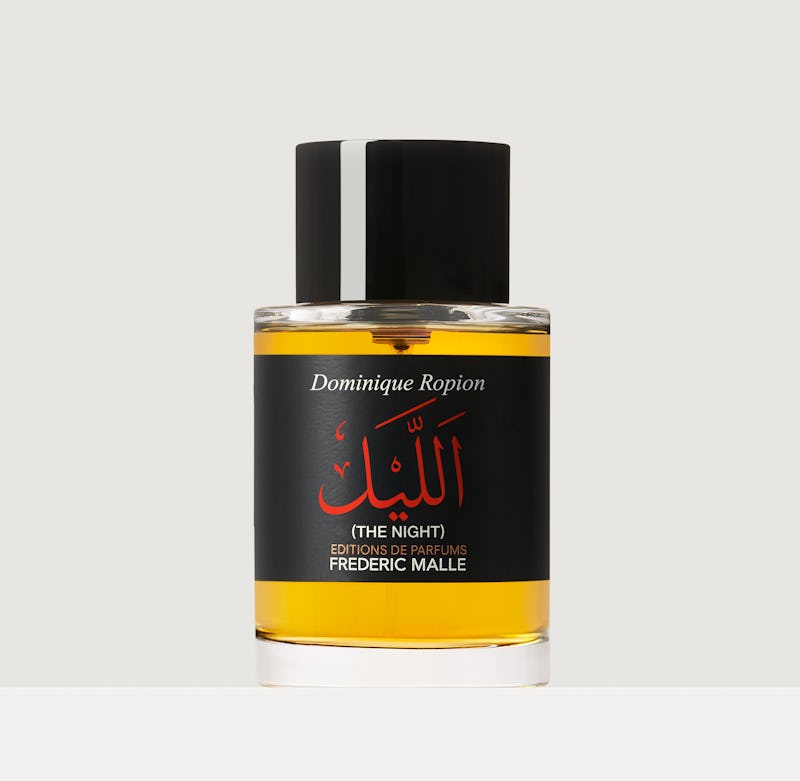

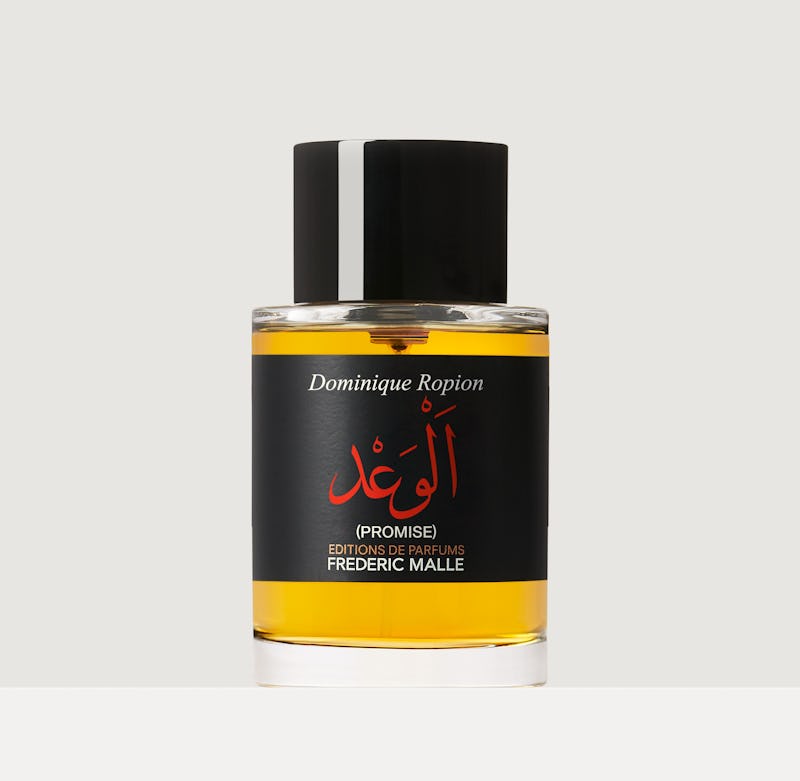

Like the great giant of American cinema, who, over the decades, made his mark on almost every genre, having directed, to mention but a few, a peplum (Spartacus, 1960), a war film (Full Metal Jacket, 1987), a horror film (The Shining, 1980), a rock opera (A Clockwork Orange, 1971), a period film (Barry Lyndon, 1975), and a science fiction film (2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968), Dominique Ropion has exercised his talents as a perfumer in a number of different fragrance families. He has composed works that speak to the time-honored archetypes of the craft: a cologne (Cologne Indelebile, 2015), a vetiver (Vetiver Extraordinaire, 2002), a floral oriental (Une Fleur de Cassie, 2000), a floral aldehyde (Superstitious, 2017), a tuberose (Carnal Flower, 2005), an oriental rose (Portrait of a Lady) and two “ouds” (The Night, 2014; Promise, 2017).

Malle then draws another parallel with cinema, this time relating to the methods of the two artists, methods that make it possible to create great films and great perfumes.

In the process of filmmaking, editing is a key element in the construction of the story and the success of a work. Meticulous and demanding, Stanley Kubrick always insisted on numerous takes of each shot, even of the most violent scenes (too bad for the actors!), so as to be able to select the best takes to use during the editing process. But the alchemy of image and story have their own laws that do not always obey logical criteria, and often Kubrick ended up including one or more shots in the edit which, theoretically, were not the best, but which worked better in the overall context of the film.

According to Frédéric Malle, the same principle applies in perfumery.

With implacable rigor, Dominique Ropion takes a very systematic approach to composition. One raw material after another, trial after trial, the choice and dosage of each ingredient is gradually refined. However, when the perfumer puts together those elements that seem to have tested the best, logic does not always prevail. And, just like the great cinematic genius, he will sometimes choose an ingredient or a dosage that in principle is not the best in absolute terms, but which works better in relation to the rest of the composition.

Frédéric Malle and Dominique Ropion photographed by Brigitte Lacombe

Malle thus suggests another parallel, between the combination of method and instinct characteristic of a Kubrick and his way of editing film, and that which Dominique Ropion applies when composing a perfume.

As the perfume publisher says, it is at this point that aesthetics takes precedence over logic, and perfumery emerges as an art in its own right.

Malle points out that it is this creative process combining rigor and instinct, the sum of a multitude of informed but subjective decisions—in short, the audacity of the artist—that makes for great works. It is this that makes it possible to constantly reinvent a theme. In cinema as in perfumery, limitless stories can be told in each genre. But only a tiny proportion of them become masterpieces, some of them true “classics.”